What do water bottles, bike parts, snack wrappers, and plastic bags have in common? They all frequently end up as trash in the C&O Canal! To date, the Trust has removed 4,725 pounds of trash and invasive plants from the park with the help of volunteers and corporate partners. As park visitation and discarded trash surges in the summer months, we are challenging visitors and community members to join us in Plastic Free July!

What is Plastic Free July?

Plastic Free July is a global movement to reduce plastic waste. It focuses on sharing solutions to reduce plastic waste in your local community to create a cleaner and healthier world. It aims to reduce waste globally by the collective actions of many individuals and communities across the world.

Ways to reduce your plastic waste in the park:

- Bring a Reusable Water Bottle

Using a reusable water bottle avoids single-use plastic water bottles that often end up as trash in the park. By planning ahead and identifying refill stations, you can help eliminate this plastic waste. Don’t have a reusable water bottle? You can repurpose a glass jar or bottle for your visit.

- Pack lunch in a reusable container

If you’re bringing lunch or a snack to the park, consider packing it in a reusable container. This avoids single-use plastics and wrappers that can get easily left behind and create trash.

- Choose canned drinks over plastic bottles

Aluminum cans are more easily recycled than plastic bottles. If you’re bringing a bottled drink to the park, consider choosing something a can over a plastic bottle. Remember to pack out your trash and recycle your can!

- Bring a reusable bag

Pack your supplies in a backpack, cloth bag, or fanny pack! Avoiding single-use plastic shopping bags on your trip will help reduce trash in the park.

If you are not able to take any of these actions, that’s okay! The most important thing to remember is to pack out any plastic or trash you bring into the park and dispose of it properly at home. By simply not leaving trash in the park, you are playing a critical role in reducing plastic waste in the park.

Looking to go the extra mile? Consider volunteering with the Trust to amplify your impact! We have many opportunities throughout the year to remove trash and invasive species in various locations along the towpath. Last year, our volunteers removed over 20,000 pounds of trash and invasive vegetation. Check out our volunteer opportunities here: https://www.canaltrust.org/programs/volunteer-programs/

Photos by Trust Staff

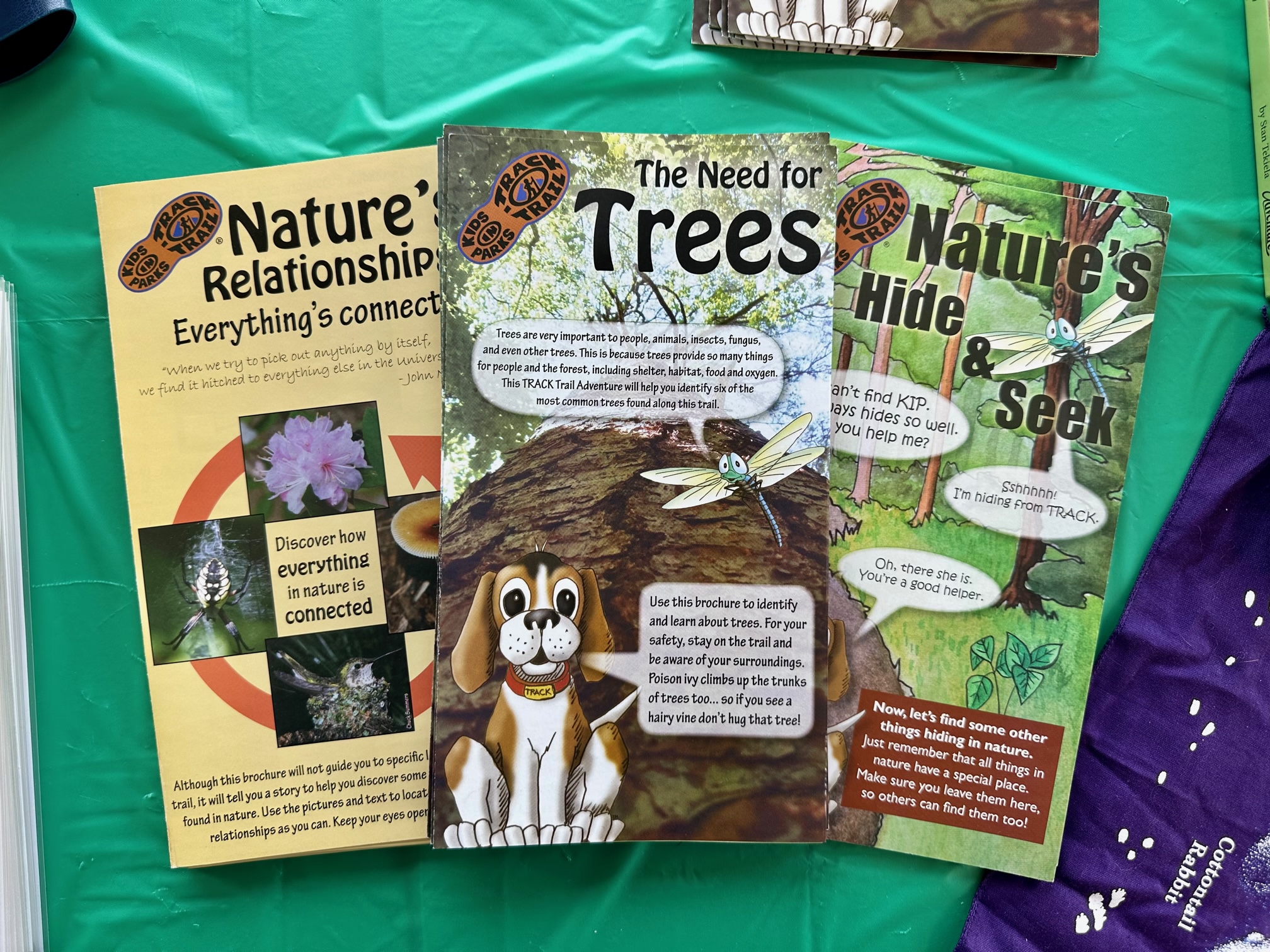

TRACK Trails is an award-winning program by Kids in Parks that offers family-friendly outdoor adventures. By following the self-guided brochures and signs, your visit to the park becomes a fun and educational adventure. As you track your progress, you become eligible for prizes.

TRACK Trails is an award-winning program by Kids in Parks that offers family-friendly outdoor adventures. By following the self-guided brochures and signs, your visit to the park becomes a fun and educational adventure. As you track your progress, you become eligible for prizes.