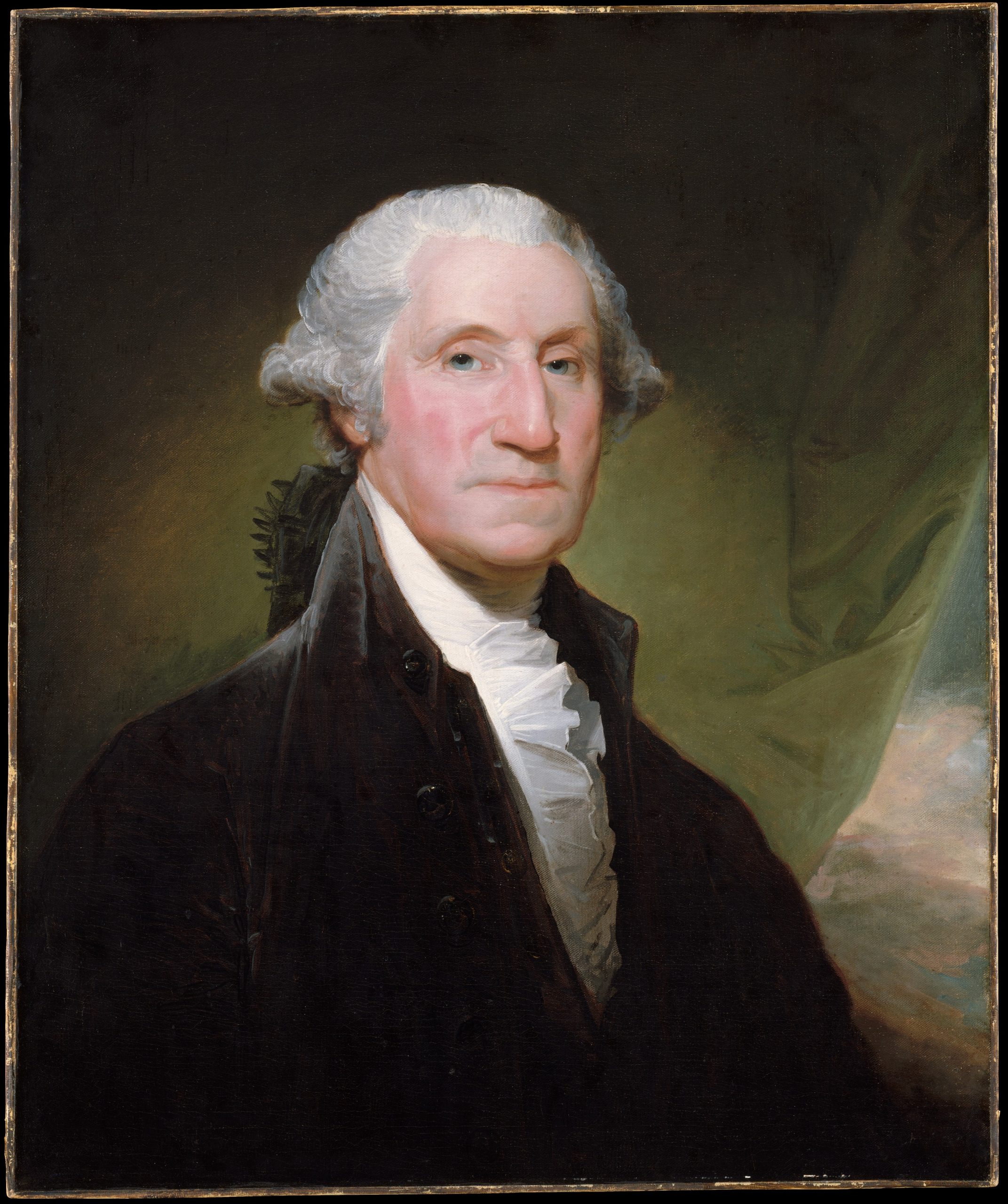

The claim to fame for every historic site – being able to say “George Washington slept here!”

Our founding father certainly got around during the early days of these United States. But did he ever sleep along the C&O Canal?

No and yes. He died in 1799 and the first try at a canal didn’t fully open until 1802. But he made multiple trips west by following the Potomac River’s path to the Ohio, where there is record of him visiting Thomas Cresap, an early settler of western Maryland at Oldtown. And of course, Washington’s Headquarters still stands in Cumberland, Md., from when Washington was at Fort Cumberland during the French and Indian War and again during the Whiskey Rebellion.

It is from this extensive exploration of the Potomac that Washington became a major proponent of the Potomac River as a navigation route to move western agricultural goods like wheat, corn, and flour to the eastern ports of Georgetown, MD and Alexandria, VA.

He had been percolating this idea since he first rode west to the Appalachian Mountains during his French and Indian War days. Washington already had a fondness for the Potomac River that flowed past his beloved Mount Vernon, and he used his western trips to check on the river’s suitability as an east-to-west waterway.

Multiple letters about the idea passed between Washington and his Virginia-planter friend, Thomas Jefferson. The idea was temporarily put on hold by a little conflict known as the Revolutionary War, which turned General Washington into a household name.

Upon resigning his commission in 1783, Washington returned to his dreams about the Potomac, mounting his horse and setting off on yet another western exploration to assure himself one last time of its suitability for navigation.

In December 1784, an article appeared in the Maryland Gazette. Although published with no accreditation, Washington biographer Joel Achenbach speculated in The Grand Idea that the author could have been Washington himself:

The opening of the navigation of Patowmack is, perhaps, a work of more political than commercial consequence, as it will be one of the grandest chains for preserving the federal Union. The western world [beyond the mountains] will have free access to us, and we shall be one and the same people, whatever system of European politics may be adopted. In short, it is a work so big, that the intellectual faculties cannot take it at a view. (127)

Not one to sit on the sidelines, Washington began writing letters to rally support for his navigation plan, and by 1785, he had gained the backing of both Maryland and Virginia governments. The Patowmack Company was chartered with Washington as President.

He and his fellow directors set to work making the river navigable. They hired one James Rumsey (who later found fame for his steamboat in Shepherdstown) as the chief engineer of the project and slaves and indentured servants to haul rock from the riverbed.

George Washington had to step aside from the Potomac project in 1789 to again serve his country, this time as its first President, but work on the Potomac navigation system persisted. He passed away in 1799, with work still ongoing.

Finally, in 1802, the Patowmack Company succeeded in their goal, opening the Potomac River to boat navigation. During the intervening years, they had built a system of bypass canals and in-river sluices that allowed boats to travel from western farms to markets in Georgetown and Alexandria.

Unfortunately, Washington’s system wasn’t as successful as he dreamed. It only worked well when the river was at a specific water level – and that level was achieved only 30 to 40 days a year. Any flooding caused tremendous damage to the bypasses and sluices, and maintenance costs skyrocketed.

By the 1820s, the Patomack Company was out of money, and in 1828, ownership transferred to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal Company, who built the continuous stillwater canal that exists today. Most of the Patowmack Company’s early construction was destroyed during the rebuilding of the new canal.

So although Washington never slept along the C&O Canal, he no doubt slept along the banks of the Potomac and dreamt about the canal that he played a role in making a reality.

***

Did you know YOU can also sleep along the Canal? Check our our historic Canal Quarters lockhouses, which are available to guests for overnight stays!

***

For those interested in further reading:

The Grand Idea by Joel Achenbach

The Potomac Canal by Robert J. Kapsch