The C&O Canal Trust is rehabilitating Swains Lockhouse to prepare it to join the Canal Quarters program. Former residents of this lockhouse, the Swain family, have decades of memories from their life in the house, when they endured several floods and crafted methods for protecting their home through necessity. Visitors can see the metal high water markers on the side of the house placed by family and various official entities. Bert Swain, who lived at Lock 21 from 1957-1980, generously shared his family memories and photos for this post.

May 1889

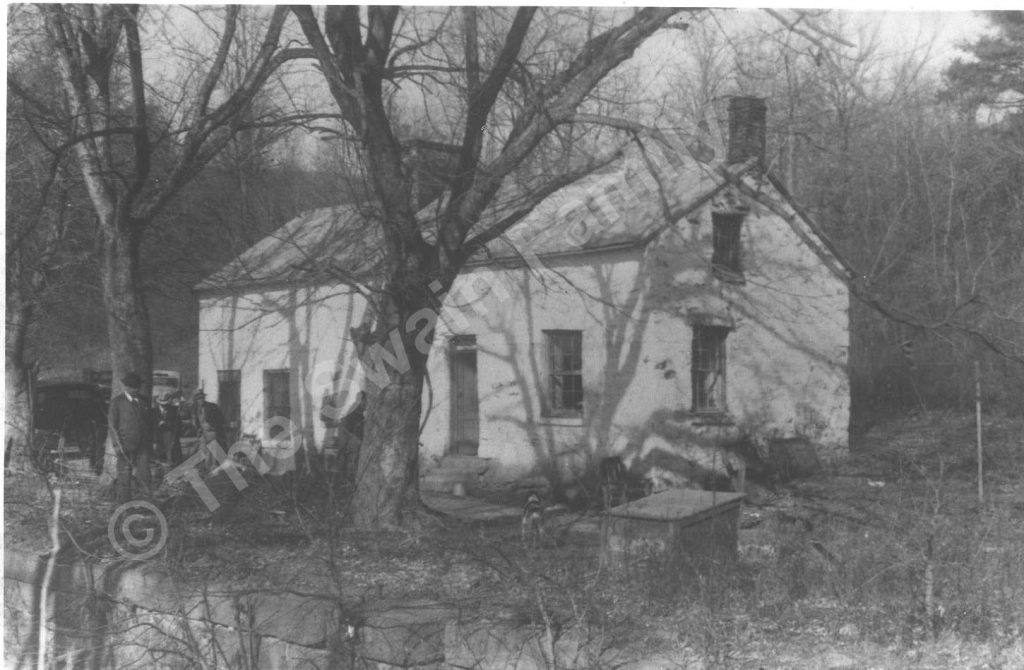

The same violent storm system that led to Johnstown, Pennsylvania’s destruction also hit the canal and the Swains hard, causing so much damage that the C&O Canal Company filed for bankruptcy and entered into B&O Railroad receivership. Bert’s grandfather, Jesse “Pap” Swain, was 20 years old during this flood, which washed away the upper end of the family’s circa 1830 lockhouse. It was later replaced, and today, you can see the difference in the sections by their height and materials.

This 1938 photo shows the expanded lockhouse. Photo © The Swain Family.

1936

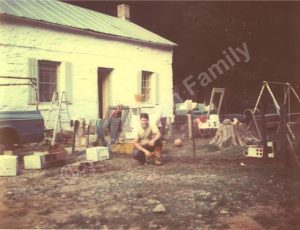

St. Patrick’s Day in 1936 saw the biggest recorded flood in the Potomac Valley, causing bridges at Harpers Ferry and Shepherdstown to wash out and extensive damage along the canal. At Lock 21, the waters reached at least 10 feet, only second in height to the 1889 flood, which crested a few feet higher. Jesse didn’t think the water would come in the house, so he stayed and did not move out their furniture. Once the waters rushed in, everything got soaked and most of it was ultimately discarded. It was a challenge to predict a flood’s crest and Jesse believed, “You feel like the river is your friend, it’s part of your family, it’s not going to do that.”

Jesse stands in the yard with most of the family’s destroyed furniture. Photo © The Swain Family

June 1972 Hurricane Agnes

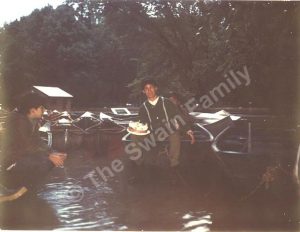

By 1972, the Swains had a thriving concessions business in a stand beside the lockhouse, where they rented bikes and boats to Park visitors. When Agnes hit, it had been 30 years since the last flood of this height along the canal. This flood was Bert’s first, and, as luck would have it, his family stepped out around 4 p.m. and were gone when things started to take a turn for the worse. Bert had two friends with him, and they handled the early stages by moving the concession stand’s boats onto higher land as the waters rose. His family returned home around 9 p.m. They used a not-so-scientific method of flood monitoring, which involved putting a stick in the ground at the river’s edge and checking an hour later to see if the water had engulfed it.

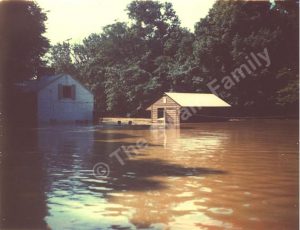

The lockhouse and concession stand surrounded by water. Photo © The Swain Family.

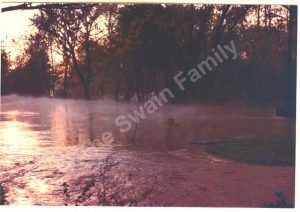

Agnes in the Evening

As evening turned to night, the water continued to rise. Bert was in water up to his chest with lightning flashing and thunder booming, helping to flip, lash, and move their boats. Recalling the event, Bert says, “It was an eerie, eerie time. Even after the rains had stopped, you could hear the rush of water and saw houses, trees — massive things you thought couldn’t be moved — floating down the river.”

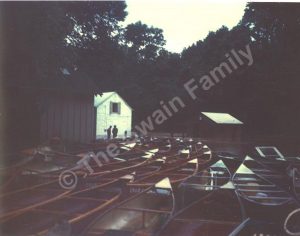

At least 20 rowboats and 100 canoes were lashed together, while 100 bicycles were wheeled up the hill to a neighbor’s garage. Photo © The Swain Family

Opening to the Water

The Swains removed the house’s doors and windows and cut holes in the concession stand to relieve pressure and allow water to pass through both structures. At the river’s crest, their home had 3 ½ to 4 feet of water inside. Any structures on the berm side of the canal that might have swept away would have traveled downstream and crashed into Great Falls Tavern.

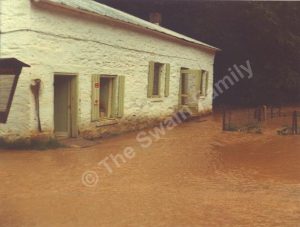

Opened doors and windows prevented the lockhouse from being swept downstream. Photo © The Swain Family

Moving Time

Around 2 a.m. that morning, the family decided it was time to move out. With the help of neighborhood friends, they cleared out the first floor and moved all their furniture to neighbors’ garages uphill on Swains Lock Road. They also had to move about 100 canoes, 20 rowboats, and 100 bicycles out of harm’s way. The boats were lashed together and were able to float over the flood waters, and the Swains and their helpers formed a human chain to push the bikes up the hill to safety.

The upper window was removed for small furniture to be tossed out. Photo © The Swain Family

Recovering from Agnes

After the flood water receded, the family put the doors and windows back on their lockhouse and turned on the heat to dry it out. The fire department brought a portable pump, which the family used to wash away river silt from the house and yard, and an uncle brought in a front-end loader to clear the debris from the parking lot. Bert remembers there being 12 inches of “gack” left behind.

Bert celebrated his 15th birthday during the flood with a cake from neighbor Pam Ramsey. Photo © The Swain Family

Recovery was a major family and community effort. Photo © The Swain Family

November 1985

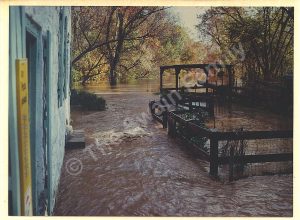

After a lengthy reprieve, the Election Day flood of 1985 caused damage that would take over a year to repair, despite the precautions the family had taken to protect their property based on their past experiences.

The water rushed over the towpath bridge. Photo © The Swain Family

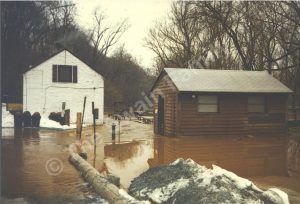

The water reached the house during the 1985 flood. Photo © The Swain Family

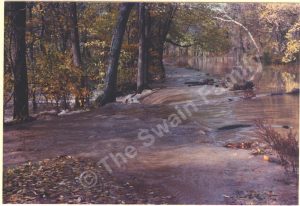

The Waste Away

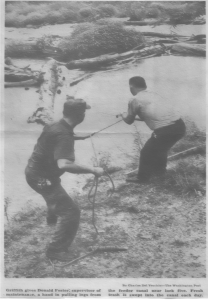

A section of the canal known as the “waste away” is the site of a former mule drink, a low part of the towpath where mules could stop for a drink. This feature was helpful for managing floods up to 15-16 feet high, since waters can flow over it easily. A Swain family task during floods was to keep the waste away clear of trees and other debris.

The waste away is being reinforced during the current towpath repair project to protect against future floods. Photo © The Swain Family

January 1996

This winter flood was devastating, though improved meteorology helped make flooding preparations more precise. Guided by forecasts, the family made the decision to leave the house windows in place.

Floodwaters reached the parking lot. Photo © The Swain Family

Family member Jimmy Butt pitched in. Photo © The Swain Family

Remembering Griff

Neighbors, friends, and National Park Service staff played a vital role in helping the family prepare, recover, and clean up from flooding events. In fact, because they were on the canal daily, NPS staff became close friends of the Swains. One of these treasured friends was maintenance worker Nelson “Griff” Griffith, who Bert had chatted with during the flood preparations for the 1996 flood. Unfortunately, Griff was killed by a falling tree on the towpath during the clean-up from that flood. A bench dedicated to him overlooks the canal at Swains Lockhouse.

NPS ranger “Griff” (left) and retired NPS ranger Donnie Foster (right) on the canal.

Though the canal is a place of beauty, it is can also be a place of danger and destruction, something the Swains and those who have worked and lived there know all too well. Their memories and expertise will help a renovated Lockhouse 21 thrive.

Morning mist floats over the 1985 floodwaters. Photo © The Swain Family

You can learn more about the Swains Lockhouse project here, and read two more blog posts by Bert Swain: Changes at Swains and Protecting the Past.

NOTE: The photos in this post are property of Bert Swain and may not be used or reproduced without permission.

*****

Did you enjoy this article? Help the Trust continue to support the C&O Canal National Historical Park by making a gift here.

Christine Rai is a college professor in the Washington, D.C. area with a passion for culture, food studies, and experiential learning. She blogs about food, travel, and teaching at www.christinerai.com.