The C&O Canal Trust is rehabilitating Swains Lockhouse at Lock 21 to become the newest addition to the Canal Quarters program. Bert Swain, who lived at Lock 21 from 1957-1980, generously shared his family memories and photos for this post about changes to the lockhouse and the family business over the years.

Changes to Lockhouse 21 and its Outbuildings

The lockhouse was built in 1830 as a one-story dwelling with two-foot thick stone walls and old fashioned lattice and horsehair under the plaster interior. The downstream half of the house is original and features irregularly cut stone, while the upstream half, which was added after the 1889 flood, features more uniform, square stones. The Swain family always kept the house’s exterior pristine, whitewashed with a mixture of lime and water. The house was shaded by large trees, which died off or were removed over the years, and was surrounded by various outbuildings used for Swain family businesses that are now long gone.

The bridge over the lock in the late 1940s did not have handrails. Photo © The Swain Family.

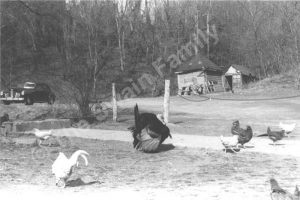

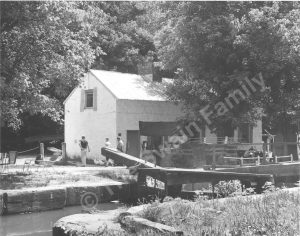

Outbuildings were placed as high as possible due to flooding. Photo © The Swain Family.

A bike storage and canoe workshop stood to the right of the lockhouse (note the barge in the canal). Photo © The Swain Family.

Justice Douglas and the Canal

In 1950, a controversial proposal was made for a scenic highway to be constructed on and along the canal, an idea supported by The Washington Post. A nature enthusiast, U.S. Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas was a champion of the canal, having spent many a Sunday hiking the towpath, and did not want to see its beauty destroyed. He wrote a letter to the Post editor, inviting him to hike the entire canal, beginning in Cumberland and ending in Washington, D.C. Eight days after the hike, the impressed editors conceded that the canal should be preserved. But it wasn’t until 1971 that the area received protection as a unit of the National Park Service, expanding from about 5,000 acres to 20,000. In 1977, in recognition of his advocacy for and relationship with the canal, the C&O Canal National Historical Park was dedicated to Justice Douglas.

Justice Douglas leads a hike on the C&O Canal. Photo: National Park Service

The Justice at Swains

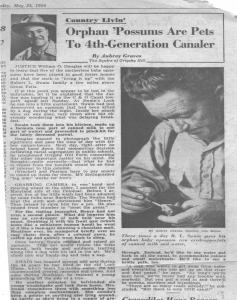

Bert’s father, Robert “Bob” Swain, and Justice Douglas were close friends due to his frequent visits to Lock 21. One morning in 1954, Bob came across a mother possum that had been killed by a dog and still had babies in her pouch. The family helped save them by feeding them a mixture of watered-down milk in a medicine dropper and finding them foster homes. Justice Douglas was out for a hike on the canal, encountered the orphans under the care of the Swain family, and passed the story on to The Washington Post.

Many in the community took an interest in the orphaned possums. Photo © The Swain Family.

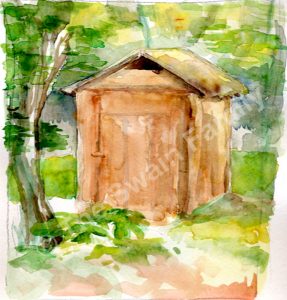

The Outhouses

Bob Swain considered the outhouse on the lockhouse side of the canal the family’s since he put in the work to build it. As the canal became more popular for recreation, visitors would use it, too, and it wasn’t always available to family members when they needed it. A family story goes that, one Saturday morning, a frustrated Bob needed the outhouse but it was occupied. He banged on the door and yelled, “Get out of my outhouse!” When the door opened, Justice Douglas emerged. Bob explained that the outhouse belonged to him since it was on the family side of the canal, not the National Park Service side. Justice Douglas said he’d look into it.

Come Monday morning, a knock sounded on the door of the lockhouse. Standing there were two National Park Service workmen, who said, “Mr. Swain, we have three outhouses here for you. Where would you like them?” Indoor plumbing wouldn’t come to Lock 21 until much later.

A watercolor of the Swain family outhouse. Photo © The Swain Family

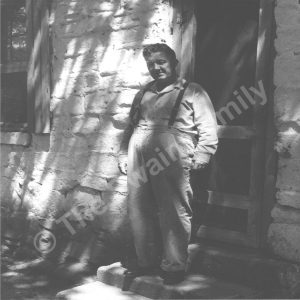

Bob Swain on the lockhouse step. Photo © The Swain Family

Swain Family Concession Business

The concession stand helped the family make ends meet as the canal transitioned from a working commercial waterway to a popular recreation destination. They rented boats to visitors and sold refreshments and fishing supplies. When Bob died in 1967, Bert’s brother “Bubba” and mother Virginia took over the long-term concession lease that allowed them to continue living in Lockhouse 21 and running the business.

The concession stand in the early 1950’s was a simple lean-to style. Photo © The Swain Family

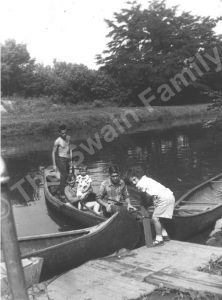

Their boat rental business started off with old fashioned canoes with ribbing and lattice, covered with canvas on the outside—“the real deal,” according to Bert. Later, the Swains added red canoes made by the family. They made a canoe form, laid fiberglass over it, added the ribbing, and closed in the ends. During this period, the kids helped mind the concession stand but would sometimes take a break to swim out to the sandbar in the river and would leave a notepad behind for people who wanted a canoe to write their name.

Bert’s sister and brother with early canoe rentals in the 1950s. Photo © The Swain Family

Another early version of the concession stand centered around a Coca Cola cooler. Photo © The Swain Family

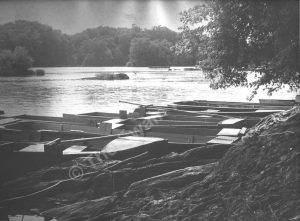

Regular customers would show up at the crack of dawn to buy bait minnows and rent a boat. The family kept 15-20 river boats for rent just down from the lock, tied with a chain or cable. The roots of the tree protruding into the water allowed them to walk down to get the boats as needed. At this spot, the river is pretty shallow, around 3 feet, so the boats were moved by poling. According to Bert, back then more people knew how to pole a boat.

Many of the Swain rental boats used a pole for navigation. Photo © The Swain Family.

Injury by Catfish

Frequent visitors to the Canal and patrons of the Swain concession business got to know the family well over the years. Even customers that were not familiar to the family could sometimes prove memorable. Bert shared that, on one occasion, a fisherman went down to the river with a group of friends. A few hours later, he came up to Bert’s brother and said, “Buddy, can you help me?” The man lifted his foot and there was a catfish attached from a fin that had stabbed through his sneaker and into his foot. Apparently they caught the catfish and couldn’t get the hook out, so they laid it on the ground and stomped on it in an effort to remove the hook. The Swains called the rescue squad, who picked the man up for treatment.

The canal was a popular fishing spot. Photo © The Swain Family.

The Miraculous Contact

In the early and mid 1960s, the Swain concession business and stand grew. Around 1963, a visitor lost his contact lens in the gravel in front of the stand on a Friday at midday. He and the Swains searched for it all afternoon, but couldn’t locate it. Saturday was gorgeous, and thousands of people lined up at the stand over the course of the day to rent boats and make purchases. Both Saturday and Sunday passed without the lens being located. Since early versions of contacts were rare and expensive, the man really wanted and needed to find it. He returned on Monday morning to search again and was shocked and delighted to find the missing contact, still completely intact, on the ground in front of the stand where so many feet had trod over the weekend.

The early to mid 1960s concession stand stood alone and had a top that could open up. Photo © The Swain Family.

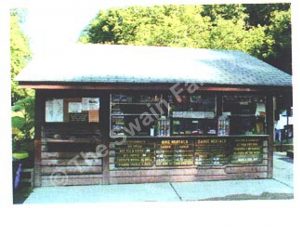

They built a new stand in 1969 which survived Hurricane Agnes and stood until 2007. Photo © The Swain Family.

John Quincy Adams

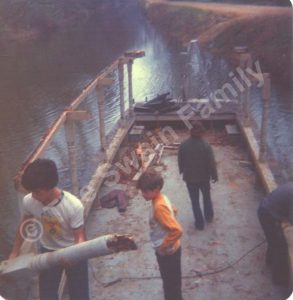

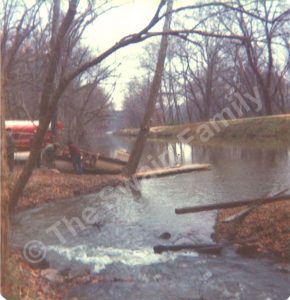

In addition to caring for the lockhouse, running the concession, and doing some light farming, the Swain family was always looking for ways to augment their income. In 1974, the National Park Service wanted a sunken excursion barge removed from Lock 21. The Swains won the bid to remove the boat and dismantled it over Thanksgiving weekend with a lot of hard work and all hands on deck. Today’s Park Service officials couldn’t figure out what had happened to this barge and were thrilled to hear Bert’s story, which solved a years-long mystery for them.

After plugging up a hole, the family began taking the barge apart (top) and then towed it out of the Canal (bottom) to be cut up and hauled away. Photo © The Swain Family.

Memories Gone and Memories Remain

Today, Lockhouse 21 is being rehabilitated into a Canal Quarters space that will be open to guests for overnight stays. Though the concession stand is long gone, the concrete pad it stood upon is still there. Other pieces of Swain family history remain too, like the flood markers on the house exterior and long-ago planted flowers that still bloom.

Bert’s father Bob and sister in front of the lock. The flowers still come up every year. Photo © The Swain Family.

You can learn more about the Swains Lockhouse project here, and read two more blog posts by Bert Swain: Fighting Floods at Swains and Protecting the Past.

NOTE: The photos in this post are property of the Swain family and may not be used or reproduced without permission.

Guest blogger Christine Rai is a college professor in the Washington, D.C. area with a passion for culture, food studies, and experiential learning. She blogs about food, travel, and teaching at www.christinerai.com.