The Potomac River and its companion C&O Canal were the northern boundary of the Confederate states. Many people fled to that boundary and the Union protection beyond it. A curious passage from Civil War Captain Michael Egan’s “The Flying, Gray-Haired Yank” reads “The post [Hancock] was also a transfer point on the “underground railway” between Maryland and Virginia, where, before my arrival, large amounts of goods contraband of war were permitted to pass with a superficial examination, or without any inspection.”

“Contraband of war”, as used by Captain Egan, might sound like illegal goods, and they were to some. The term was used by the Union military to refer to groups of African Americans escaping enslavement. Coming north during the Civil War, they risked their safety, seeking life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness under the protection of the Union Army troops.

“Contrabands Escaping”, Edwin Forbes, Library of Congress

Freedom seekers traveled through Hancock, Maryland and points along the C&O Canal to enter Union states. A large refugee encampment gathered in Harpers Ferry, on the southern side of the Potomac River from the C&O Canal. The local Union commander would not allow them to pass over the canal and beyond it to Maryland. While waiting there, the contraband refugees aided medical staff at Clayton’s hospital and “contributed to the function and support of military operations” (from Contraband: Prize of War 1862). However, when Colonel Miles surrendered his Union forces to Confederate General Jackson in September of 1862, every African American man, woman, and child who had not hidden well enough was removed from Harpers Ferry and returned to local enslavement or loaded into railway cars to be enslaved further south. Estimates vary between 1,500 and 4,000 African Americans who were sent back into slavery from Harpers Ferry. In contraband camps, there was always risk.

“Contraband Camp – Harper’s Ferry, Va”,

John P. Soule, Library of Congress

Quite often, Union army encampments were neighbored by contraband of war camps. The residents of those encampments “dug, ditched, planted, weeded, hoed, harvested, hauled, distributed, laundered, cooked, nursed, scouted, and more for the Union War effort.” (Contraband Camps and the African American Refugee Experience during the Civil War | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History. While soldiers were divided in their opinions about the end of enslavement and racial equality, the formerly enslaved were not. They worked to support the Union camps and cause, sometimes without payment.

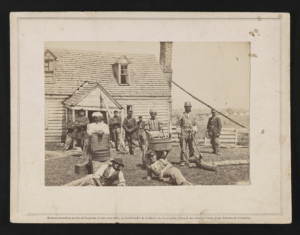

“Contrabands at headquarters of General Lafayette”,

James F. Gibson, Barnard & Gibson, Library of Congress

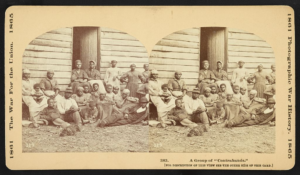

The needs of the refugees were met by the Union military, which prioritized its soldiers. Charitable organizations also contributed to alleviate difficult living conditions. Donations of clothing, food, and funds were offered by many, including Frederick Douglas, President Abraham Lincoln, and his wife, Mary Lincoln. While simple food and shelter were often provided, the freedom seekers relied heavily on their own devices and efforts to meet their basic needs. Cold and hunger were often present. Fortunately, there was often access to education for the first time. Another benefit was employment. Of greatest value was the comfort of enjoying the family and community security that had been denied them by slavery. In spite of the difficulties of camp life, freedom was worth it.

“A group of ‘contrabands’”, James F. Gibson,

Library of Congress

Works Cited

Egan, Michael. “The Flying, Gray-Haired Yank; or The Adventures of a Volunteer.” Philadelphia: Hubbard Brothers, Publishers. 1888

Forbes, Edwin. Contrabands Escaping. 1864. Library of Congress, no LC-DIG-ppmsca-20701 (digital file from original item), https://www.loc.gov/item/2004661467/

Gibson, James F. A group of “contrabands”. 1862. Library of Congress, no LC-DIG-stereo-1s02760 (digital file from original stereograph, front), https://www.loc.gov/item/2011660086/

Gibson, James F. Contrabands at headquarters of General Lafayette. 1862. Library of Congress, no LC-DIG-ds-05120 (digital file from original item, front)

Harpers Ferry NHP. “Harpers Ferry National Historical Park – Contraband: Prize of War 1862 | Facebook .https://www.facebook.com/harpersferrynps/videos/contraband-prize-of-war-1862/327988231868734/

Keckley, Elizabeth. “Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave, and Four Years in the White House”. New York: G.W. Carleton & Co. 1868

Manning, Chandra. “Contraband Camps and the African American Refugee Experience during the Civil War”. Oxford Research Encyclopedias, American History. 19 December 2017. https://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-203

Soule, John P. Contraband camp – Harper’s Ferry, Va. 1862. Library of Congress, no LC-DIG-stereo-1s04358 (digital file from original item, front). https://www.loc.gov/item/2015647582/